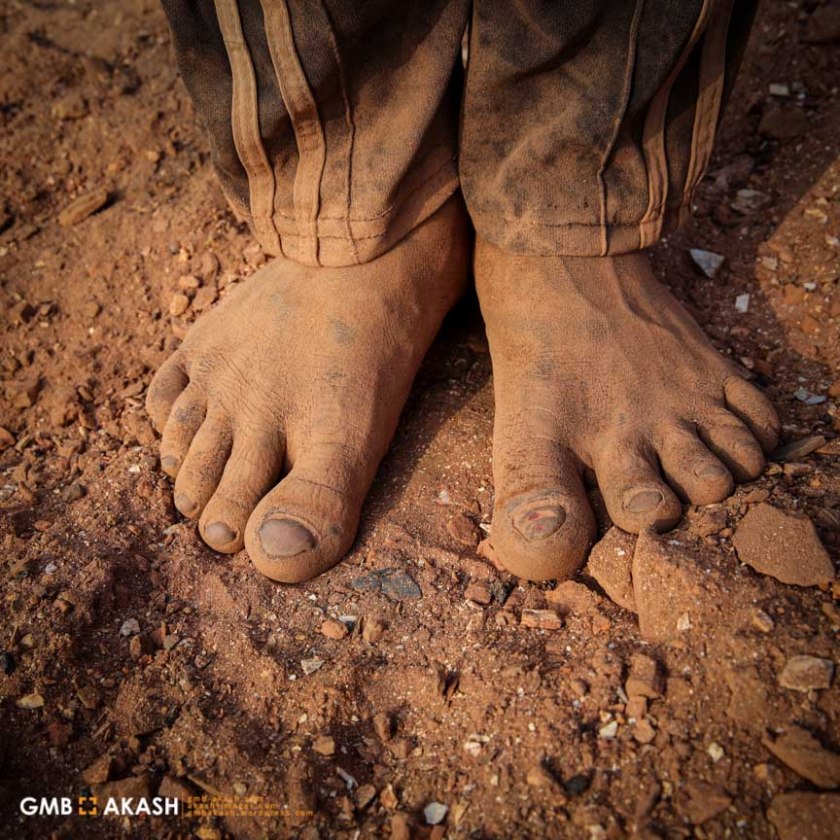

Brick field labouer’s feet tell their tales. Thousands of men, women and children continue tolling in the open brick fields. Their muddy clothes, smudged coal colored skins and bare feet tell the tale about how everyday they are fighting to live a life. I continue to search their stories of struggle about how their hope transform into despair. Once a labourer stopped me to take his portrait and asked me to take an image of his feet and said, ‘Show our feet. It’s enough to explain what we are up to.’

Under the baking hot tropical sun, Moriyum (7 years old) continues to collect coals in the most perilous conditions even though everyone goes to lunch. Just after shifting 1000 bricks to dry in the sun, Moriyum’s brother Mohsin (9 years old) also goes to lunch. But Moriyum continued to collect coal for her family.

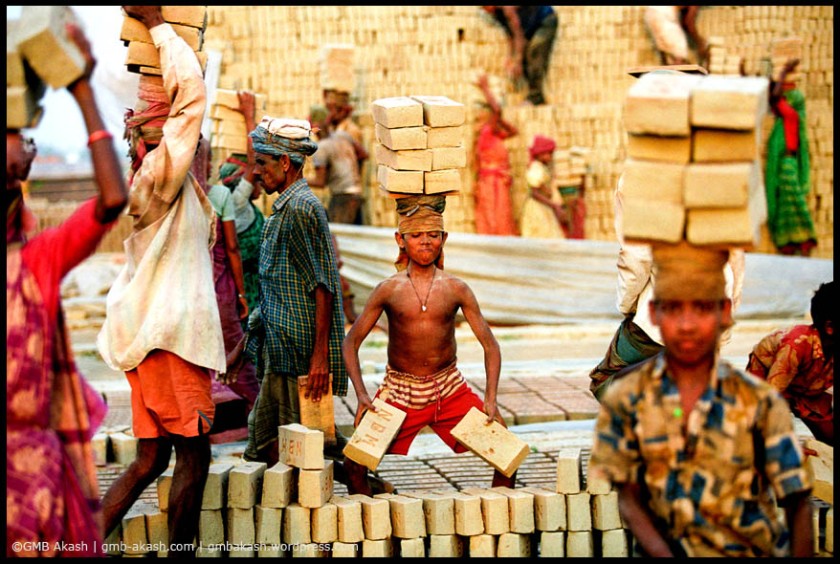

Working children are a common sight at the brickworks as they regularly employ entire families – who oftentimes make their homes on site. Education is a luxury for Bangladesh’s rural poor with children often earning their keep as soon as they can walk. Ranging in age from young children to grandparents, they work long hours to mix out millions of bricks to fuel construction boom that shows no signs of abating. The high chimneys of brick fields are snot only pouring grey smoke into the air but also blowing it into labourer’s lungs. All of the brick fields are located along rivers. Millions of bricks are burned here. Almost all bricks are made using a 150-year-old technology. Soil is mixed with water, formed into bricks using wooden forms, then left to dry in the sun before being burned in traditional kilns. The process is done almost entirely by hand.

Kohinoor who was balancing the heavy loads atop her head said, ‘We work like slaves. And we die like slaves.’ Kohinoor’s mother-in-law died last year while working in the brick filed. Another woman who has worked a decade in the field was badly suffering from tuberculosis and headaches. Kohinoor added, ‘We know we will die by working here, but we have no option.’

Brick-making provides a better income than agriculture or other jobs available in rural Bangladesh, but it is dangerous and often devastating to workers’ health. Accidents are common and workers have no protective gear except save for what they are able to cobble together themselves.

By balancing the heavy loads atop their heads, workers must carry the raw mud to the brick making area are where skilled artisans shape it using brick moulds filled by hand. However, the millions of workers who make the bricks face harsh and uncertain conditions. Brick field labourer Makbul said, ‘Everything tastes like mud. I taste mud in my mouth, tongue, throat everywhere.’ By showing the feet of Makbul’s friend, Jasim said, ‘We are brick human. We have feet like coal.’

Like Makbul and Jashim, hundreds of men come with their families during the brick session in the brick fields. They made their temporary shelter near the brick field in the place given by the brick field owner. The mud house’s bed is made by brick after brick and then putting plastic over the bricks where they rest and sleep. They took loan from the brick field owner which and continue to pay it back by giving labour with full family. Small children of each family works to dry thousands of brick every day. For drying 1000-5000 bricks a child gets 25-50 taka daily. That also goes into the pocket of father for buying food for the family. The Father and mother of each family go to work before sun rise. They carry 12-16 bricks each weighting 2.5kg. For a twelve-hour workday during which an average worker carries about five thousand bricks, he earns Tk. 80 after his expenses are paid. This means toiling 12 hours a day for a daily wage of 120 taka (USD 1.70) for men and 100 taka (USD 1.40) for women.

Still they hope for a better life and perhaps dream of happiness. During his break, after lighting a cigarette Motahar said, ‘My wife often asks me to take her to the cinema. We have no money left after basic shopping at the bazaar and paying loans. But she managed to save and bought an old phone for me. Now while I work, I listen to songs.’

(Brick fields are not only causing suffering for labourer but for the environment also. Bangladesh is hit harder than almost any other country in the world by climate change despite emitting very little greenhouse gases. But still the emissions from the brick kilns hurt the environment. Brick kilns are the leading cause of air pollution in the country. There are about 5000 brick kilns in Bangladesh, which are largely responsible for air pollution. Dust from the brick-making sites spreads in the wind to nearby towns and villages clogging the lungs of young and old and generates health problems that the country is ill-equipped to handle. The chimneys continue to poison labourer lives and as well as letting the environment to suffer in silence)